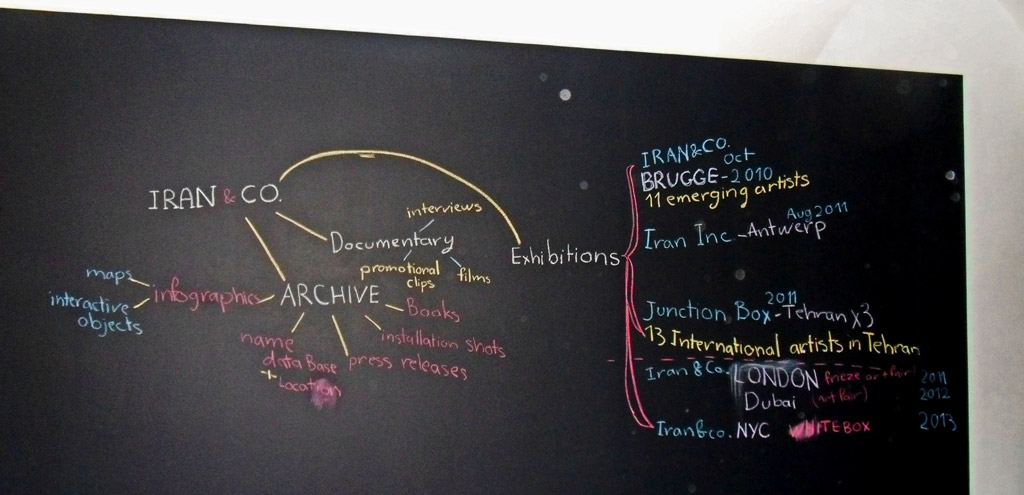

Through our endless correspondence and the thoughts we shared, the exhibition and archive gradually transformed into the multi-layered project Iran & Co. Michel Dewilde and a number of other enthusiastic individuals also participated but, from the outset, we decided not to rush. Instead, we planned to simultaneously follow our multi-dimensional research in different stages and along different paths.

One of the paths is that of the interviews. We began making these at the Dubai Art Fair in March 2010.The related films are, at present, a work in progress. The interviewees were chosen from a large group of curators, collectors, gallery owners, critics and experts and from a broad range of artists, from established and emerging stars, to artists who had been side-lined. We wanted to get to know the creators and contributors within the Iranian contemporary art world and to listen to their unique ideas and thoughts, their future aspirations and the current anxieties caused by the recent market-driven craze for Iranian art.

As part of our ongoing survey, the other task that lies before us is the compilation of a register of the exhibitions of Iranian art held outside of Iran. Often, the exhibitions were orchestrated for European and North American audiences and, of course, the influential Iranians in the diaspora. In the absence or malfunction of state institutions, and with a lack of private investment within the country, some people tried to gain power by founding their own institutions and related communities. There were frequent attempts that ended up disintegrating because of factors such as restrictive regulations, customs policies and the soft censorship mentioned earlier. The archive covers the events of the last decade and, when analyzing the material, it is clear that several factors influenced the creation of these exhibitions, including the downfall of the Eastern bloc, the search for an alternative other to blame for every potential future risk or imaginary foe, the shock of September 11th and the subsequent surge in Neo-Orientalism.

At first, the role of the Iranians in the formation of these exhibitions was neutral. It would not be unfair to call it passive. However, after the regime change in 2005, the power structure inside Iran shifted. These sociopolitical events gave the whole scene a new rhythm and sense of motivation. Why? It’s crucial to know, because it obviously forced artists to think anew. For those who were being spoiled, and to some degree manipulated, by the outstretched hand of the Institute of Visual Arts and the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Arts, it was a shock. It thus marked the beginning of certain sorts of survival strategies. On the other hand, there were people who refused to take risks with their careers and who silently continued their practice, often in the margins, back in their studios or in small galleries.

At the beginning of the 21st century, in the first half of the decade, the so-called cultural approach was the driving force behind the organization of most of the exhibitions that took place outside of Iran. Slowly, as the investment in art increased and the expansion of the Internet grew in Iran, catalogs and websites gained more significance in terms of numbers and quality. A swarm of eager individuals and the board members of various institutions flew towards Iran with high hopes and a kind of fidelity. Dealers, agents, intellectuals and critics followed. Nor must we forget the journalists and reporters who tended to base their writing upon a few days spent in Tehran and other big cities. From this they created a patchwork that included a mixture of Iranian contemporary art, women’s rights issues, underground music and homosexuality. Thus a new set of counter-stereotypes was incorporated within the existing ones and the claim was made that it represented the other.

Iran, the one that you never see or hear about in the news. It’s a new way for someone to make a name for him (or her) self and earn some money.

In the second part of the decade, it is possible to trace the effect of political turmoil and the ups and downs of different economies on both a global and a regional level. In this era, the exhibitions tended to be wrapped in more sophisticated layers of clichés and kitsch. However, despite all the care and the theoretical trappings, the clichés were nearly always exposed.

The research into the representation of Iran beyond its border gave us the opportunity to make a quick

sketch, a croquis, which just happened to be based upon the records that came to light and what the witnesses described from their own perspective. It was not meant to judge the entire scene or predict the future. Rather, it was a group attempt to gather evidence from the shattered field. We wanted to try and trace the nature of representation by putting the pieces of the puzzle together, side by side, on a flat surface. We acknowledge that it is still too early to apportion blame and yet too soon to close the files. It’s going to be a long investigation that requires the participation of many researchers, and it will take time to analyze all the random discoveries alongside the systematically filled databases. But the result will be something that is almost totally lacking in Iranian art: documentation.

The team invites scholars, thinkers and potential patrons to step in. With their contributions, it will be much easier to create a multimedia website and publication based on the archive of Iran & Co.

Posted by Amirali Ghasemi, Tehran

Hi, this is a comment.

To delete a comment, just log in and view the post's comments. There you will have the option to edit or delete them.